Shawn Kittelseon’s Heart Attack operates in the tradition of romance classics like Romeo and Juliet, but it’s also informed by up-to-the-minute issues like police militarization. A self-confessed pop-culture omnivore, the Mortal Kombat writer recently sat down with us to discuss the long journey his sci-fi epic took from idea to graphic novel (available this week!). Here’s what he had to say…

How do you describe Heart Attack to the uninitiated?

Heart Attack is a story about teenagers who are living in a world where a pandemic has leveled society in a number of ways. The way out of the pandemic was a new gene modification technology that led to the rise of a generation of people who have variant DNA.

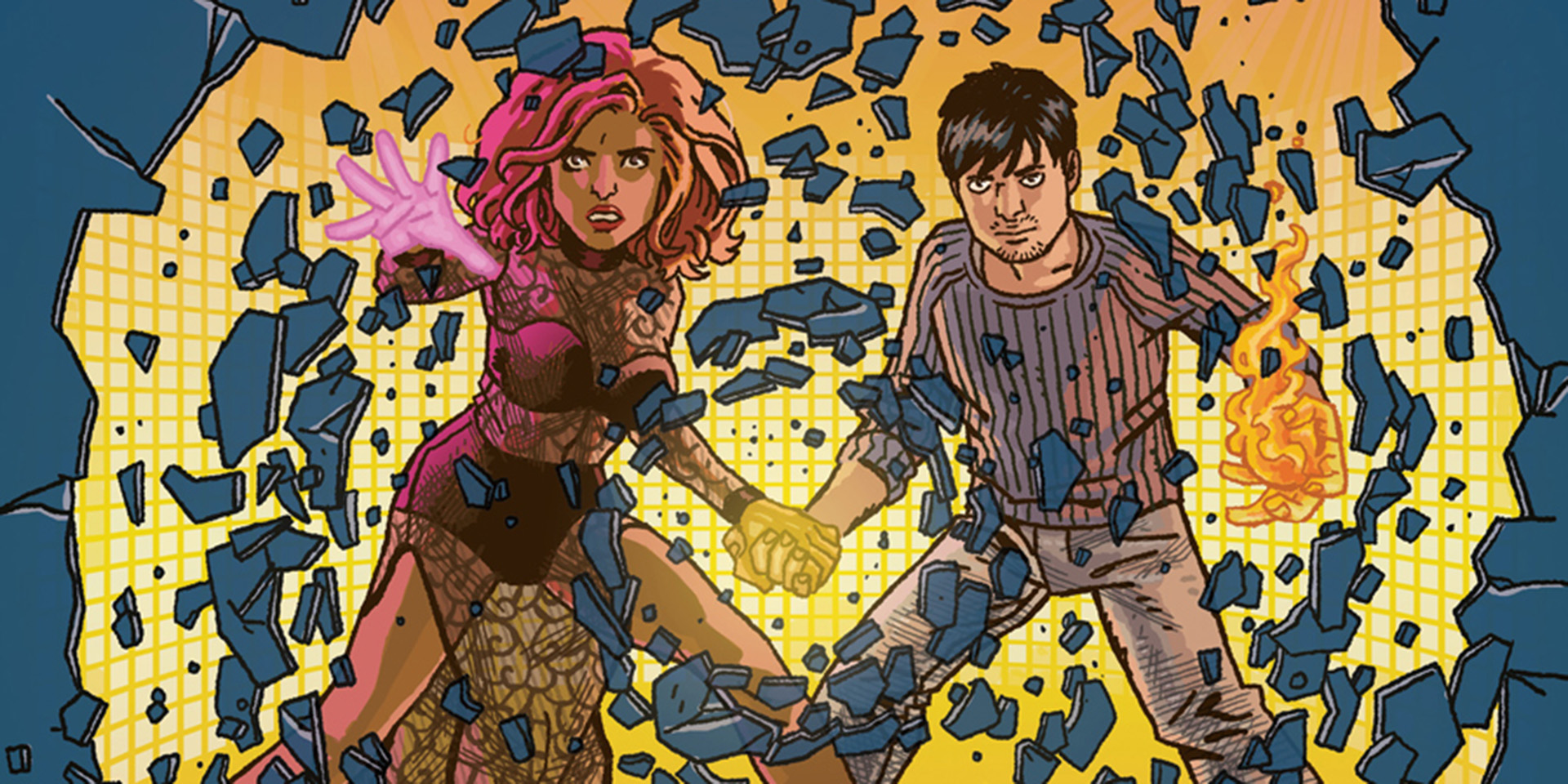

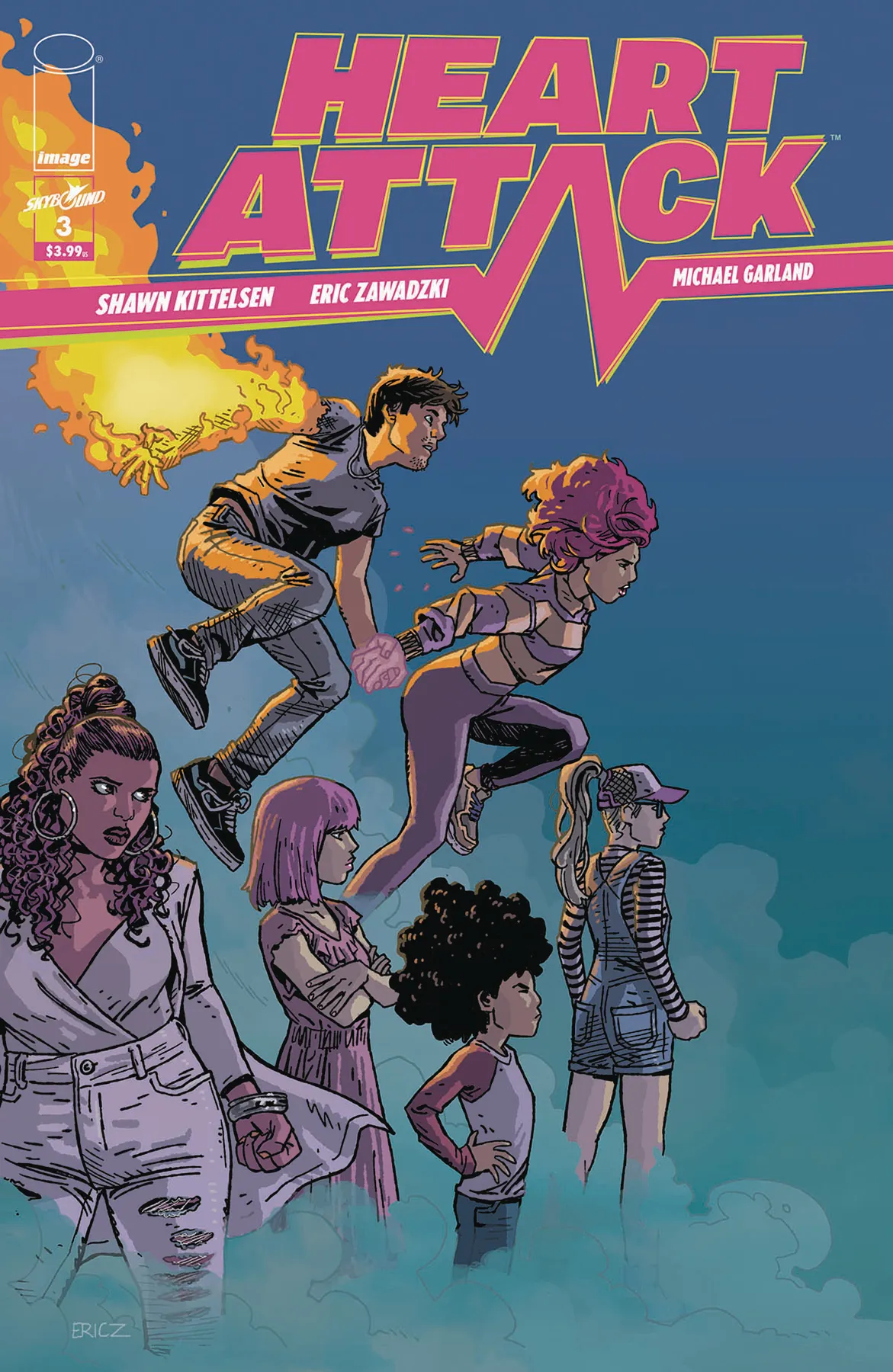

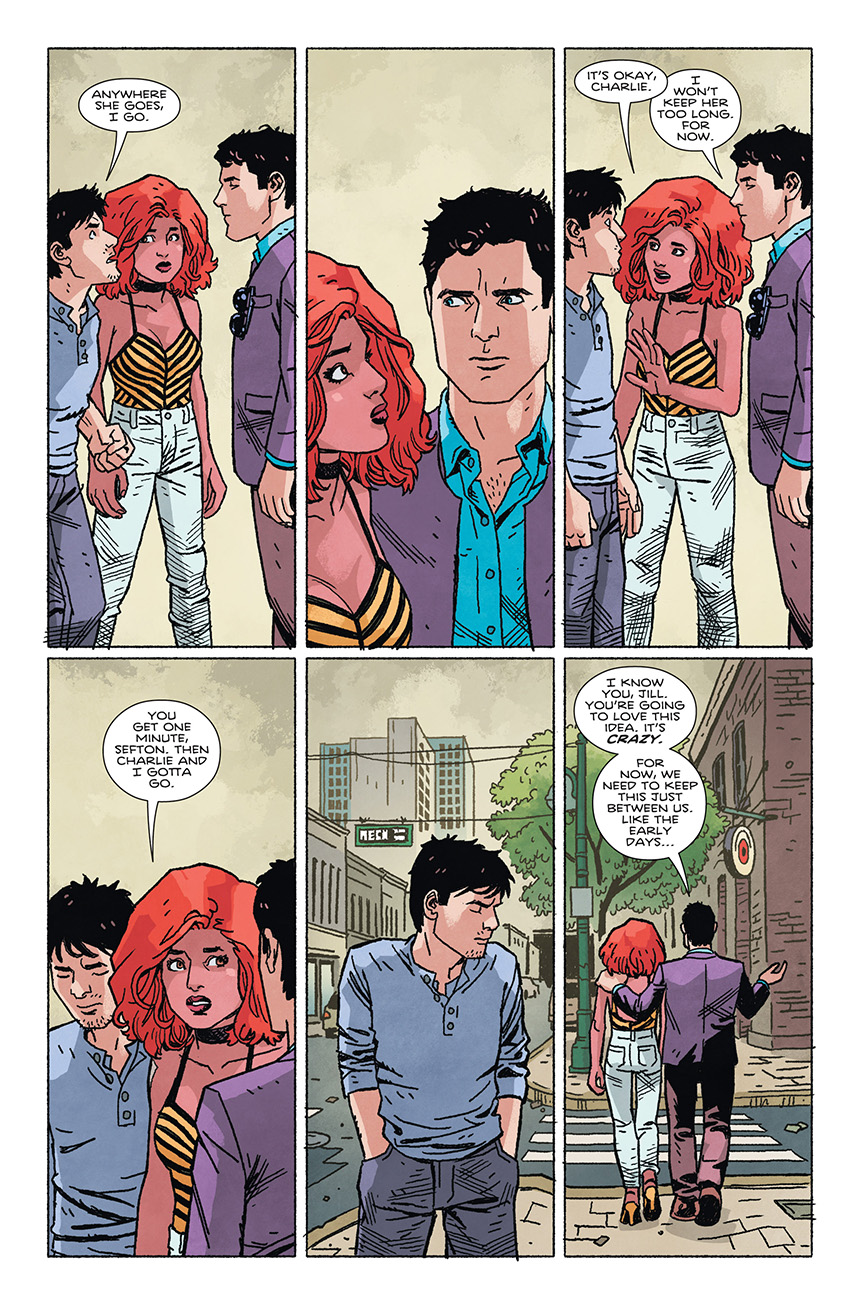

So they’re technically something other than human and as a result they’ve been denied human rights. The teenagers that we meet in the story are two such variants who are being denied their human rights. One of them, Jill, is a young activist. The other, Charlie, is not an activist, not a part of the movement. When they meet, they find that whenever they touch, they have this incredible power. Because most of the variants have something special they can do. They have their variation.

But they don’t have superpowers in a traditional comic-book superhero sense. They can do really subtle things. Like, instead of throwing a fireball, they can just make their hands really warm. Instead of telekinetically picking up a car, maybe they have tactile telekinesis where they can touch something and motivate it differently.

But when Charlie and Jill touch, they have what in the world they call PMDs, or powers of mass destruction. Even though they come from two very different places in this world and have very different views on their status as variants, they are now linked and have the power to radically change the conversation and change the society around them.

But you can’t just punch a way out of that problem. And no matter what powers you have, how do you use them to change the world when people are afraid of you? What if there’s no Magneto to fight? What if there’s not some big beam shooting out of the sky that you have to save the world from? How do you prove to people that you’re not a threat?

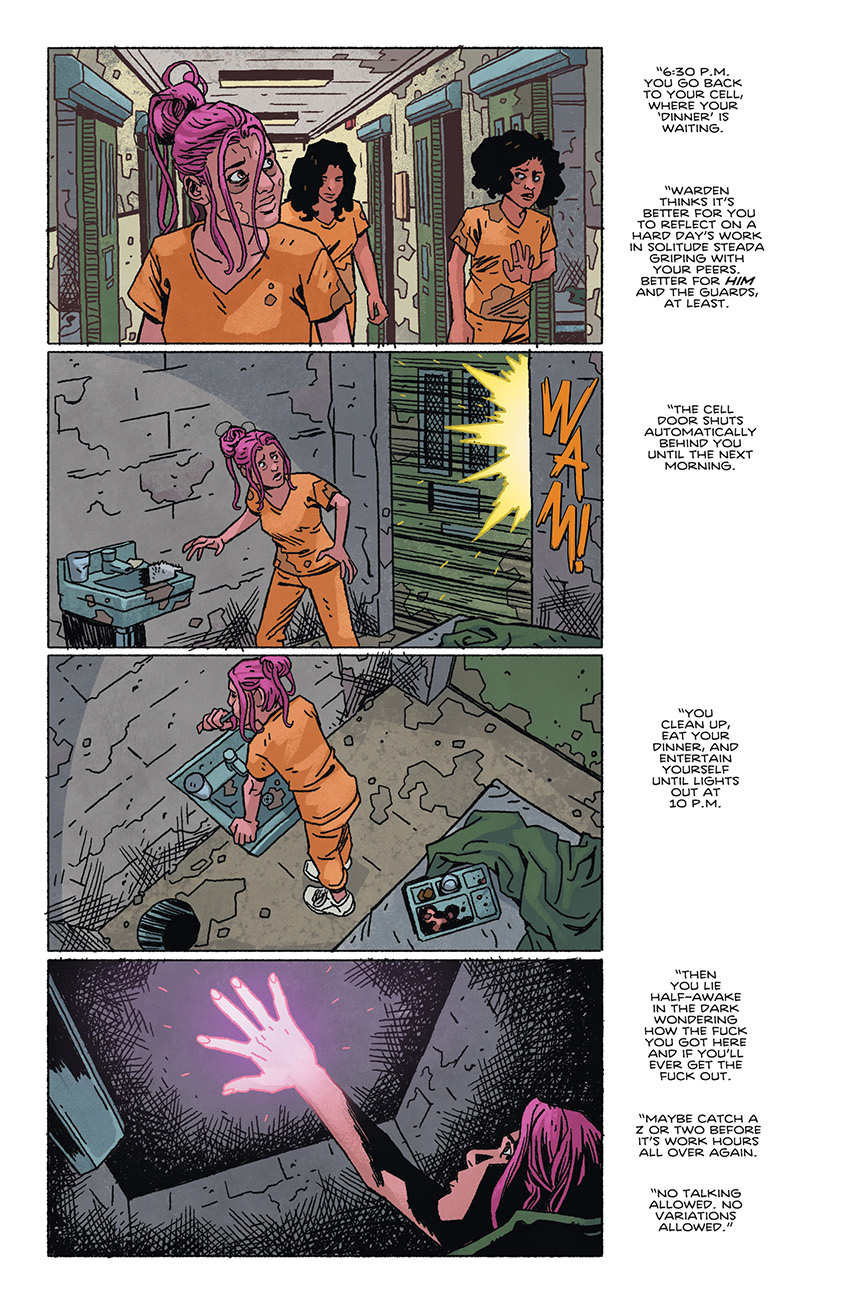

So they live in this very complicated world that’s a lot like our own where there are a lot of politics at play and there are politicians and groups of people who are afraid of variants and think they should all be stacked into prisons and work camps. Then there are people who are supporting variant rights, and believe that variants should have the same rights as everyone else, even if they have these abilities. It’s a complicated book, but at its heart it’s a love story about Jill and Charlie and the way that they find each other in this world where everyone else is at odds and they have this power to change things.

One of the nice things about Heart Attack is that it touches on so many topical issues, including the pandemic, but it’s never ham-fisted or preachy. Were those issues weighing on you when you conceived of Heart Attack or did they arise as you wrote the story?

When I first started thinking of the story, it was 2012, which now feels like a very different world from the one that we live in. At the time, there were a few things that were really interesting to me. One is just… I’ve always been a fan of YA fiction and a big fan of romantic movies and romantic comedies. I knew I wanted to write a romance, and I knew I wanted it to focus on younger characters. And I wanted to write something that was very different from the video games I’d written. Because a lot of the video games that I’d worked on were really core superhero things. The larger social issues of the book were things that I was always very concerned with.

I started my career as an editorial assistant for Douglas Rushkoff, who’s a media theorist who has written all kinds of books on media bias and viral media, as well as corporatism and what we would call “team human.” The difference between people who are rooting for some singularity where we give ourselves over to technology and upload ourselves into the digital future versus people who believe in the value of real space and real reality. So I always had these more esoteric interests and concerns. But they really converged.

Can you give an example of one of those convergences?

I saw a movie called Death Squad. It’s a Brazilian action movie, and it was about a real-life group called the BOPE. The BOPE appeared to me almost like a real-life Judge Dredd. A hyper-militarized group that is built to take down criminals and drug cartels that are brutally violent and dangerous, but that themselves end up oppressing poor communities and committing insane acts of violence like on the streets. I was curious about the reality behind that. The more that I dug in and the more books I read and documentaries I watched, the more it occurred to me that the militarization of police in South America was really mirrored in the U.S. by the rising militarization of police, by the rise of SWAT teams.

You see stories about police buying military-grade weaponry and military-grade vehicles and the sort of ever-escalating tension in America – if the criminals have all these guns, then the cops need to have bigger guns, and then everybody just keeps getting bigger guns. So it occurred to me, “Oh, we’re not that far off from Brazil.” We’re trending in the same direction.

I’d actually already written a version of the first arc, and then Michael Brown was killed and there was the unrest in Ferguson with protests, riots, and a whole national conversation. At that point, the book suddenly went from becoming “What if in the future things go in this direction?” to hyper-relevant. I had so many thoughts about it. Should I change the book? Is this suddenly touching on something that’s too real? But it felt like maybe this was the book for this time. Then it just took a longer time for the book to get made. I would stop to work on a video game. Or it took us a while to find Eric [Zawadzki] as an artist and co-creator to work on it with me.

So, over the years, it was shaped and informed more and more by current events, but we finished writing and drawing most of the art for the book in 2019, well before the pandemic. So the whole pandemic angle and the idea of using genetically modified vaccines, that was a little creepy when a real pandemic came, and we needed vaccines and people didn’t trust the vaccines and had all these questions about things. The political division that we saw in this country became so much more cartoon-like. Suddenly, again, the book just kept taking these turns, where I thought I was showing folks a vision of a near future, and it turned out to be a lot more contemporary.

There was a lot of sensitivity that I had to write the book with. Just thinking about… How are people going to see this relative to what they’re already seeing on the evening news? What are they reacting to? That involved a lot of research, a lot of attending protests, understanding political activism and good trouble versus just outright domestic terrorism and stuff like that.

It’s just wild to me. I never imagined we’d live in a time where being anti-fascist was considered a bad thing, or even remotely controversial. It’s like, “Wait, if you’re not anti-fascist, are you… pro fascist?” There’s a lot of people that are like, “Yeah, we are.” That was new.

You’ve worked in a lot of different media. What was it about this story that made it so well suited for comics?

You’ve worked in a lot of different media. What was it about this story that made it so well suited for comics?

Well, initially, the very, very first take on the story was a lot more action-focused. The powers of mass destruction were going to go a lot bigger. Skybound Editor-in-Chief Sean Mackiewicz called me up and said, “Hey, there’s something in these first two issues, these first two chapters, that’s really working well. The rest of the story goes in a much more action-focused direction. But when we’re focused on Jill and Charlie and their relationship, even though that’s at the core of the story in any version, the more focus that we put on it, the better it feels, the more unique it feels.”

So we had already decided to have the powers more grounded and try to treat the world as very real and very grounded. But, bringing that focus back to Charlie and Jill kind of relieved me of pressure that I was putting on myself to make some big action book, because I thought, “Well that’s what I do with a comic.”

It changed the way that I think about writing for comics in general. It became much more of the personal YA book that I really wanted it to be, but I was afraid that I didn’t have the ability to write. Because I was coming from such a blockbuster superhero games place.

Having worked in so many different media, you clearly have a very broad love of pop culture. When you were growing up, was there any one medium you drifted towards more than others? Or were you just a sponge for everything?

I’ve always been kind of an omnivore. If I have a day where the family’s out and I’ve got no work I need to be working on because it’s Saturday or something, I always have a moment where I just can’t pick — do I read a book? If I do read a book, do I read a comic or do I read prose? If I read prose, do I read fiction or nonfiction? Do I listen to music? Well, what genre of music do I want to listen to right now? What’s my mood? Do I watch a movie? Do I watch a TV show? Do I play a video game? Do I play VR? Do I use the Steam deck?

I kind of go down a rabbit hole. The more content that’s out there, the harder it’s been to kind of triage and prioritize. Like, what do I want to watch? [Laughs.] A lot of times I end up getting into the thing that feels most relevant to whatever I’m working on. But whenever it’s for pleasure, it’s still really hard to choose. It’s not that I have no attention span. It’s more that I have a very broad interest. I want to know as much as I can know and see as much as I can see. I’m drawn to new things and new rabbit holes. Research is just like candy for me. I can spend all day in a library basement, looking at primary source documentation. Diving deep into history.

It’s kind of ironic that, for all the research you do, one of the key influences for Heart Attack apparently came about by accident…

Yeah, I was on a flight. I was working for, an ad agency at the time, so I traveled a lot for that job. Someone in the seat next to me was watching Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo and Juliet on their iPad. So there was no way for me to put it on my screen, but I watched it. It didn’t even have the subtitles on, but because I know the play really well – I’d studied a lot of Shakespeare – I just watched it silently for most of the ride.

I had something else going on my own screen, but I kept getting distracted. By the end, I’m crying for this movie that I can’t hear, that I’m looking over someone’s shoulder at, being totally creepy probably. [Laughs.] But it caught my attention and reminded me the story was really powerful and stayed powerful. Between Romeo and Juliet, West Side Story, even things like Warm Bodies, I’m just a sucker for star-crossed lovers. So it occurred to me, “Why don’t I write a story like that?” The initial kernel of the idea was “What if it was Romeo and Juliet, but one of them was a superhero and one of them was a supervillain?” The more that I thought about that, the more I was like, well…

In real life, you wouldn’t have superheroes and supervillains if you had real powers. So I started going down the rabbit hole… What if powers were real? And what if two people fell in love in this world and there was some social chasm between them that they had to cross? That became the story of Heart Attack.