An idiosyncratic artist who brings his distinct style to every project he works on, Tri Vuong has crafted two acclaimed titles for Skybound: Everyday Hero Machine Boy and LEGO Ninjago: Garmadon. As part of our ongoing series of interviews celebrating APIDA Heritage Month, we sat down with the writer-artist and learned how he channels his point of view into every project, regardless of how independent or mainstream it may be. Here’s what he had to say…

How did you first discover comics?

My first exposure to comics was actually not Superman or Batman or anything North American. I was actually in Hong Kong when I was three or four, and saw Chinese translations of Ultraman, a lot of Super Sentai, that kind of thing. I couldn’t read at the time. I was only three or four years old, but the imagery really left an impact on me. I moved to Canada pretty soon after that, when I was around five, and just kept on reading whatever comics I could find, which was then Spider-Man and Superman and a lot of the superhero stuff. So it was sort of this weird East meets West amalgamation. It really got deep in my bones. That definitely is reflected in Everyday Hero Machine Boy.

When did you decide to pursue art as a career?

Pretty late in life, actually. I always drew. I was always that kid that in class that drew a lot. But I didn’t think it was an actual, viable career option. So after high school, I tried getting into computer science. I thought, “Yeah, that’s the practical thing. Computers are the future. I could do that.” But I was just really bad at it. I thought “That’s what I should do,” but it’s not what I really wanted to do.

I had to fail pretty hard out of that. I spent a couple years soul-searching. “I seem to be really bad at what I thought I should be doing. I should try this art and this comic thing.” I went into animation school and learned to draw, and that was a much better fit for me. I don’t think I completed the transition until my mid to late twenties. It was pretty late in life, all things considered.

What were some of your other key art influences?

It was really a kind of wonderful journey of discovering new things and then rediscovering old things. Like I said, I discovered a lot of the Japanese stuff first. And some of the eastern stuff kept on popping back in. I remember Robotech came out and I was like, “This looks so familiar.” [Laughs.] The style, I couldn’t place it because there was no internet back then. But I was like, “These big eyes and these spiky hairdos and these cool robots. This seems so familiar to me.” So I would go on a deep dive into that. But then, after going too far into that, I would get into the Disney stuff, Glen Keane and the old animators. There’s just like so much stuff to find. Back when I was younger there was no internet, so any cool thing you could find was like a like a treasure. So I just worked even harder to uncover more of whatever cool set my brain on fire at the time. Then after that there was Bruce Timm’s Batman: The Animated Series. That was like, “What am I looking at?” You know? Every couple of years another thing would pop across my eyeballs and change my life.

How did you make the leap from fan to professional?

My first pro job was actually in the video game industry. Just getting paid to do art was amazing. My first big break would be when I sort of decided to stop being a studio artist and start drawing. It was a great experience. I learned a lot. But telling stories was what I was really interested in. I did a web comic called The Strange Tales of Oscar Zahn. I did it for no reason other than I thought it might be fun to try to make comics. It organically developed a following online, and that was the thing that changed everything for me. Because if it didn’t work out, I’d probably just go back and try to get another job as an animator or a character designer.

What led to your collaboration with Irma Kniivila and Skybound Comet on Everyday Hero Machine Boy?

One of Skybound’s editors, Arielle Basich, she discovered The Strange Tales of Oscar Zahn, and I guess she liked it or saw something that was interesting. So she emailed me out of the blue, saying, “Hi, I’m from Skybound. I like your work. If you ever wanna pitch anything, I’d love to see what you do.” I was like, “OK, that’s a cool opportunity there. I’ll just sort of gonna put a pin on that.” Around the same time, my studio mate Irma and I had made this short story about a little robot boy, for no reason. We finished a 10-page short story. Then I started connecting the two – “Maybe this could be a pitch!” I sent it over to Arielle and said, “Hey, we did this thing. What do you think?” It started there.

How would you describe Everyday Hero Machine Boy for those who haven’t read it yet?

To be really reductive, I like to think of it as a coming-of-age tale. Like Astro Boy meets Spider-Man with a dash of Dragon Ball Z. Mm-hmm. So, in essence, a little robot boy falls to Earth one day. Tragedy ensues because of his actions, and he ends up killing an old man and being raised by the widow of the man he accidentally caused the death of.

It’s a fun tale, but it also deals with real feelings of grief and of finding your place in the world. I think there’s something in there for everyone. Even though it’s marketed towards middle grade, we didn’t gear the comic specifically to that age. We just had some things to say, and it came out in this package.

One of the things that’s great about Everyday Hero Machine Boy is that as much as it is influenced by Astroboy or Spider-Man, it never feels derivative of them.

I’m really glad you said that. We only knew this stuff after we finished it. Because when we were doing it, we were just drawing from feelings and vague memories of things that we loved from childhood. So it’s more like nostalgia for the things I’ve said as opposed to a direct line. It’s a little bit more mixed up, and it came out a bit rough because it’s our first comic. We had to learn a lot to together. But I like to think that something really authentic came out of that and, and it seems like people respond to that.

Part of it is the collaboration between me and Irma. By myself, I would not have thought, “Oh, we should make these bullies a duck and a chicken!” It’s so silly, right? But when you say it to a friend and they’re sitting right next to you and they laugh at that idea, it’s like, “Wait a second. That was funny. Maybe we should pursue this together, and maybe there’s nothing more to it.” Whereas, if I was by myself, it’s like, “Why would I do that?” So you kind of have self-censorship. We were each other’s audience. So I was writing for Irma, and Irma was writing for me.

Was there a rhythm to how the two of you collaborated?

Yeah. It is kind of hard to describe, because back then we literally sat right next to each other, and we were both capable of writing and drawing and coloring. Anytime one person was stuck on something, we could just hand it over to the other person to finish the thought or have a tackle at it. Even if we couldn’t quite solve the problem, the person who had taken the ball would be able to carry it further, or at least in a different direction that the first person couldn’t quite see. So it was neat to hand things back and forth like that. We had our own strengths and weaknesses. I would say we both co-wrote it, but I think Irma had the first pass at the story, drove it back to me, and then we’d go back and forth. Then I drew it. But even my pencils, sometimes they’re really heavily based on her layouts.

Sometimes, because we could both do everything, we did butt heads too. Because we’d be opinionated about every single aspect of it. [Laughs.] So sometimes things would grind to halt until we sorted that out. [Laughs.].

So Irma wasn’t generating pages of scripts so much as she was presenting her writing in the form of thumbnail layouts?

At first. That really helped in the beginning when we were just building this world. But eventually we had to write scripts, because it was just too time consuming for us to lay out these things. So it was like, “OK, we need to learn how to write actual scripts because the editing process is much easier in script form.”

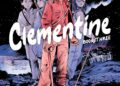

Your LEGO Ninjago book with Skybound, Garmadon, is a great example of how an artist’s individual style can shine through even when dealing with branded, model-sheet characters. There’s a wonderful scratchiness to its lines.

What you bring up was a bit of a concern for me, because they asked me if I’d be interested in doing something LEGO. I’m like, “Hell yeah!” That’s such a big part of my childhood, to get a chance to work with that franchise is amazing. But I did have the exact same worries. These are very blocky, geometric characters, and it’s very difficult for me not to be loose and kind of wonky. I actually brought this up with Sean [Mackiewicz], the Editor-in-Chief. He said, “Well, how do you envision this? You’ll draw a LEGO, but you’ll just draw it in your style.” Hearing that freed me. It’s like, “OK, I’m gonna draw LEGO the best I can draw LEGO, but I’m just gonna forget that I’m drawing toys and treat this as if they were, like, Smurfs. They’re not plastic in my head. I don’t know what they are. Maybe they’re made out of marshmallow. They’re almost like hobbits or something. They just happen to look this way and I’ll just treat them like regular people rather than plastic with decals.” Then I would trust folks at LEGO to tell me when I was going too far, and I would always go a little bit too far. But surprisingly I think they were really okay with a lot of things that I thought they would not be okay with.

They were like, “OK, we’ll just scale it back a little bit. This is breaking the mold too much. The eyes are maybe a little bit too different.” But they really put the story first. And there are also tricks. Knowing the limitations of that franchise helps, because you can work your way around it… I needed a scene of them sitting by the campfire. They can’t sit cross-legged. So you kind of stage things, like “OK, I’ll hide them in shadows. I’ll stage it in such a way where you see the thumb through the canopy of trees or something.” Then nobody ever thinks about it. Nobody’s ever questioned, “How is it possible for them to do that?”

How aware of LEGO Ninjago were you before making this book?

I didn’t know a lot about Ninjago before this. I watched it with my nephew. Boys that age, they were just obsessed with it. But then, because I was gonna write the story, I watched every single episode and some seasons I watched multiple times. It was like, “Well, I wanna do my due diligence. I want the fans to be happy.” But halfway through I really became a legitimate fan. It clicked for me – “Oh, this is the way I felt about the Ninja Turtles or Transformers!” This is the modern equivalent of that, you know? It’s got all these cool elements, just like the things we loved.