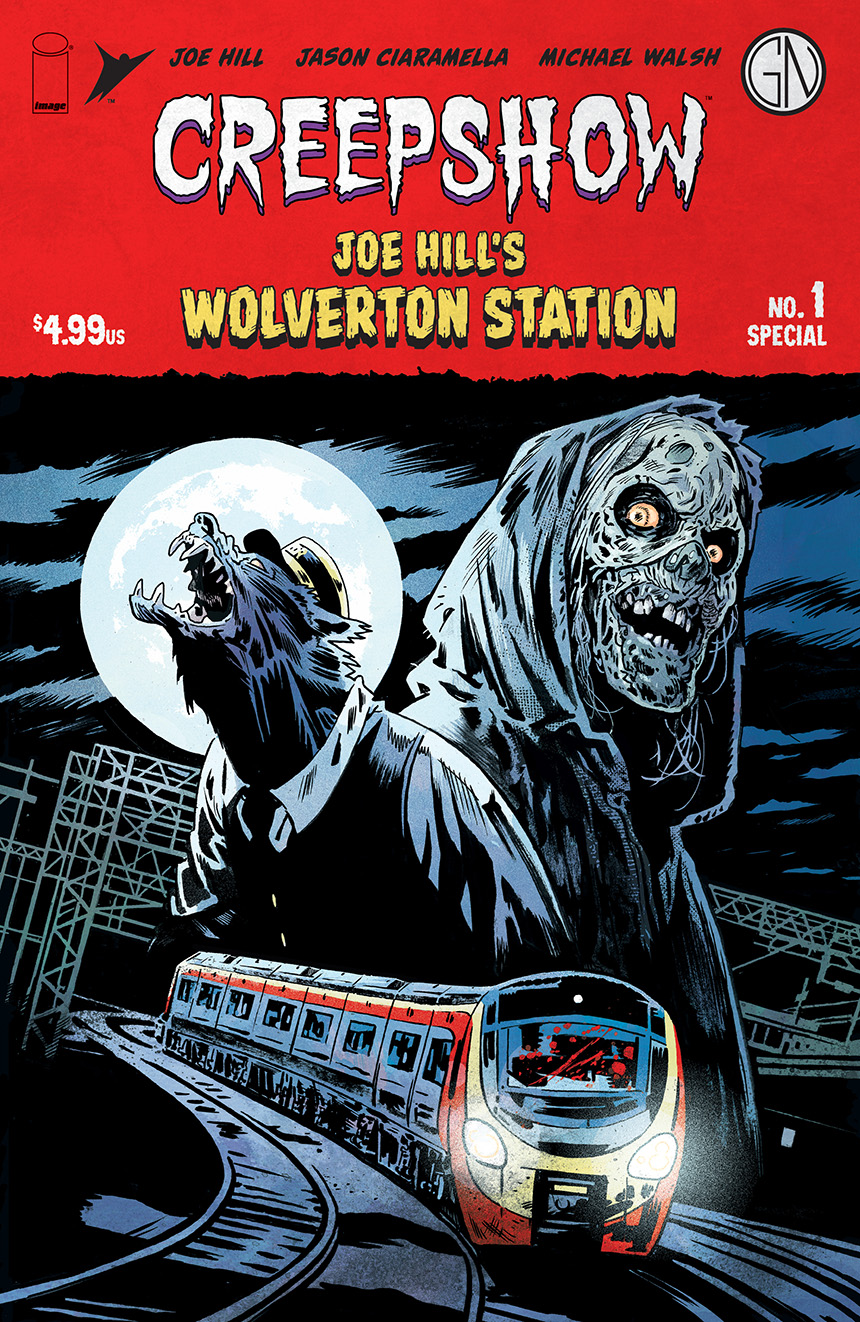

One of the most acclaimed horror scribes of the 21t century, Joe Hill has terror baked into his very DNA. The son of the legendary Stephen King, Hill – at nine years old – appeared in the original 1982 Creepshow; as the boy in the anthology film’s opening and closing segments. He’s since won every award from the Eisner to the Bram Stoker for his fiction, which has been adapted for Greg Nicotero’s new Creepshow series on Shudder. So it’s entirely appropriate that Hill has found his way to Skybound’s Creepshow comic via next year’s Creepshow: Joe Hill’s Wolverton Station, adapted from his acclaimed short story by Jason Ciaramella and Michael Walsh. We recently sat down with Hill to discuss Wolverton Station, the legacy of Creepshow, and his love of all things horror…

When you were nine years old you appeared in the original Creepshow film. Then as an adult your short stories were adapted for TV’s new Creepshow. Has Creepshow helped shape your career as a writer?

When I was at the formative age of about 13 or 14, and really connecting with comics, in a way only a 13-year-old boy can, the comics I loved wasn’t the stuff coming out at the time. My dad had hardcover collections of all the EC books. He had Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, Two-Fisted Tales. There was even a hardcover collection of the EC pirate stories, Piracy, and of psychology stories, Psychoanalysis.

I think I encoded some ideas about how a short horror story is supposed to work from repeated readings of those hardcovers. At the time I had already long since stopped thinking about the formative experience that was being in the first Creepshow movie. But now I can see, it’s not so surprising that I would connect with the horror stories, the horror comics, the great horror comics of the ‘50s and ‘60s as strongly as I did. Because, of course, those were exactly the comic books that inspired the Creepshow film in the first place. That was this thrilling sort of formative experience for a small child.

So, even to this day, whether it’s in comic books or just in prose fiction, I’d say a third of the horror stories I write or a third of the fiction I write is scary high-concept setup and then a punch line. Which is always that last turn of the knife, which is what made those stories work. If the wife-abusing husband loves bowling, by the end of the story, she’ll be bowling with his severed head. That’s how those stories work. There’s a gross-out elegance in that, that I’ve always responded to. Also a sort of cosmic-like beauty – it’s like, “Oh, if only real life was that way.” [Laughs.]

I talk a lot about how humor and horror are two sides of the same coin. The example I always use is… If you watch Bugs Bunny smash Elmer Fudd over the head with a sledgehammer, you laugh. If you see Leatherface do it to a teenager and blood squirts on the camera, you scream. But you’re actually responding emotionally to the same scene, right? By the same thinking, a lot of short stories of horror are constructed like jokes. The punch line is that decapitated head and the bowling bag that the deranged woman is using to throw a strike. So there is a part of me when I start writing a story that’s like, “Is this a story that has a punch line? Is this a story where there’s a payoff? The bleak, cosmic shout of laughter at the end of a particularly horrifying tale?

Wolverton Station is very much constructed along those lines. From the beginning, we’re with someone who has a cosmic comeuppance. We have a guy who thinks of himself as quite a wolf among sheep. But then he finds himself in among the real wolves and discovers just how vulnerable he himself really is. I love that kind of thing.

The story has one of the most novel uses of werewolves in recent memory.

Thanks. It’s funny, because I didn’t know I’d be such a werewolf guy. I’ve visited with werewolves and comics before, because I wrote a backup feature for the Hill House titles called Sea Dogs. I was pondering the Revolutionary War. I was trying to think how the Continental Army was able to defeat the British Empire, which had the greatest Navy the world had ever seen at that time and the most disciplined fighting force. The only reason I could think of why we were able to win the Revolution was werewolves. So wrote a story about three werewolves sneaking aboard a 70-gun ship of the line and wreaking havoc. So I guess I do like to play with the hairy guys.

I’m also a dog guy. I’ve had dogs for years and stuff. I have a doodle now, and when he stands up on his back legs to look out the window, he looks like a very small man in a dog costume. There’s something unsettlingly human about him. Like I always say, “Outside of a dog, a book is a man’s best friend. Inside of a dog, it’s too dark to read.” I stole that from Groucho Marx. [Laughs.]

You steal from the best. [Laughs.] Going back to Creepshow for a minute… Did that film also help spark your love of writing different media? Because at a young age you were involved with a movie that utilized both the comic medium and that of the short story. Is that one of the reasons your comics draw as much acclaim as your prose fiction?

It’s a very kind thing to say. I hesitate to try to unpack my own psychology, but there is some kind of thread there. I recognize that there’s a thread that begins at the age of eight

on the set of Creepshow and being looked after by a young Tom Savini. I spent the week that we were shooting on Creepshow with Tom Savini in his trailer, because they didn’t have any kind of on-set babysitting. So he was the on-set babysitter. Tom looked after me while he had movie stars come into his trailer, and he made them up with grotesque injuries and he worked on his monsters. So there’s something that begins there with my childhood friendship with Tom Savini, that then passes into becoming a comic reader in my teenage years, who was almost exclusively fascinated by horror comics and loved horror films. The one magazine that I read reliably cover to cover was Fangoria magazine, which came out monthly. That was my Life magazine. That was my Sports Illustrated. Then it goes all the way to my professional career, where I was actually a comic-book writer before I was a novelist, and figured out how to write a horror comic before I figured out how to write a horror novel. So, you know, I’ve certainly always been comfortable swimming in different kinds of media, whether it’s working in TV or working in comics, or writing novels or writing short fiction.

I’ve also talked, in other places, about the farming theory of the imagination, which is… You got a couple of acres of imaginary territory, and the way to keep the soil fresh is to work on a cycle where there are different crops coming through every season. So you will have farm-raised corn one year, barley another, then soy a third; and then let them go fallow for a year. By the same theory, I do a novel, and then I do a comic book, and then I do short stories, and then I do a screenplay, and then it starts again. Each thing seems like a fresh challenge hasn’t become rote. I’m not just phoning it in. I’m not just going through the paces. I’m excited because I feel like, “Oh, this is new. This is the new thing that I’m doing, and it’s nothing like what I just did,” because the form itself is radically different.

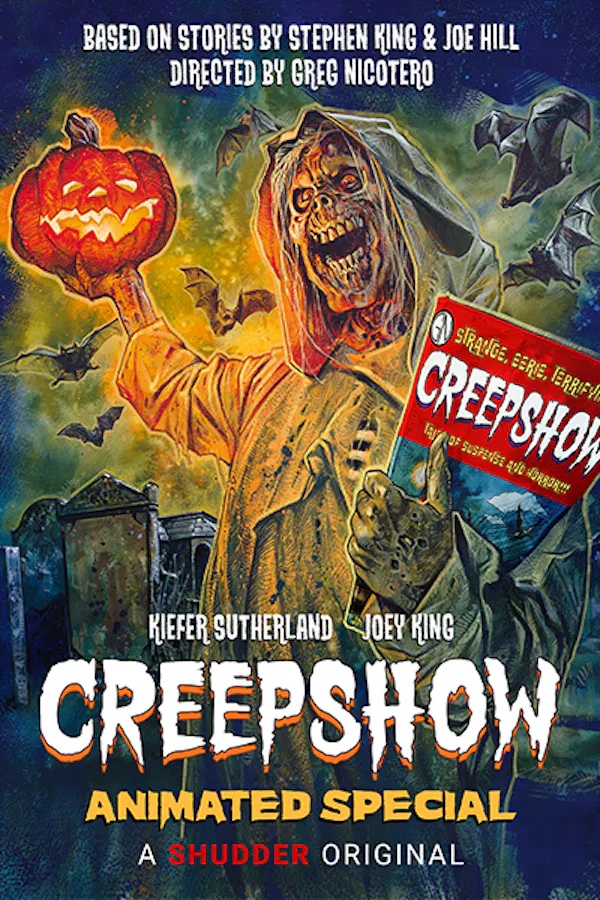

When you find ways to fuse those forms together, it’s especially fascinating. To date, the most memorable installment of TV’s new Creepshow is an animated adaptation of your “Twittering from the Circus of the Dead.”

I gotta tell you… I’ve been lucky to have a few things adapted. I was fortunate to be writing high-concept fiction during peak TV. So there’s lots of stuff that has been inhaled and made into TV shows or movies, especially if it’s got a high concept behind it. If I was going to list out my three favorite adaptations, it would probably be “The Black Phone,” maybe followed by “Twittering from the Circus of the Dead.” Because it so perfectly captures what I was going for in the story. It has great narration; it is the story completely brought to vivid life. The zombie circus performers were designed by the great comic book storyteller Eric Powell, who did The Goon. He came up with the zombies. And when I was writing the short story, that’s what I was imagining. I was imagining Eric Powell zombies. So to see it on the screen was terrific. I also thought it was very amusing. The actress Joey King did the narration and she’s wonderful, she’s just great. She puts a whole bunch of feeling into a great performance. But I always thought it was funny that Greg Nicotero wanted an actress named Joey King to do one of my stories. I didn’t miss the joke, and it was fitting. [Laughs.]

Another thing that’s unique about your work, among that of contemporary horror writers, is that it appeals to both the gorehounds and the literati…

I think that has more to do with the times than anything I’m doing in particular. When I came into publishing, when I was beginning, horror, the genre itself, was actually looked at as a very third-rate field. There wasn’t much happening there. Publishers had retreated from labeling stuff as horror fiction because they thought it was death in the marketplace. But there’s been a shift in the last decade. Suddenly, horror is cool again, and some of that is because of all these critics who have celebrated elevated horror. Films like Hereditary. Horror has been in tune with the times, it has been able to address big themes in a way that more mainstream art seems not to have been able to. I would look at a film like Get Out, for example, as saying things about race in America that mainstream filmmakers had been struggling to express. Horror was actually a more effective tool for exploring some of those ideas.

I’ve always cared about how my sentences sound. It’s always mattered to me that characters are psychologically unique and interesting. That they feel real, but also not rote. That you’re spending time with people who are almost like mysteries, like puzzles begging to be solved. I have I have cared about the craft side. So I think in an era when horror fiction

has been sort of revived and is commercially viable and, critically, getting a second look, I’ve benefited from being in the right moment, and then doing stuff that has at least some literary aspirations. Although I’m basically a Creepshow guy at heart. [Laughs.]

Do you think the term “elevated horror” is a useful one for broadening the genre’s appeal, as opposed to creating a new form of segmentation?

I think it’s fair to say that there is some horror that’s incredibly scary and effective and well done. Vivid, intense – like the Elizabeth Moss remake of The Invisible Man – that’s elevated horror but it’s not pretentious. And it’s powerful. It’s about the way women are gaslit in abusive relationships. But it does all the horror stuff well. It may have a big theme, and it may have big ideas and stuff, but it scares you as well. It’s a really well-constructed thriller. I think it’s fair to recognize that something like that, or maybe the movie It Follows, is doing one thing, and then a movie like Deadstream, which was a Shudder release, is a silly, gory, blood-in-your-face gross-out. I mean, it is located somewhere between Return of the Living Dead and a Looney Tunes cartoon. It’s really funny and it’s really gory, and all the characters are a little bit exaggerated. It’s fair to say that movie wasn’t made to win awards. It was just made to entertain your pants off. It was just made to give you a shout of laughter and a good couple of good screams.

The only thing I would say is it’s not like someone invented elevated horror ten years ago. Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde is elevated horror. The Haunting of Hill House and “The Lottery,” those are works with elevated horror. Scary fiction has always been able to punch with the best of them. So, yeah, I’m not offended by the term. I would even say that there has been this movement towards horror with big ideas, and when it works, it’s great. It’s really fun.

Can you talk about what you’re working on now? What’s next for you?

I’m revising a novel called King Sorrow. I’m working on the third draft of that now. That’ll be out in early 2025. I wish it was gonna be sooner, but the publishing pipeline is what it is, and it takes a while to bring a book to press and to launch properly. So I’ve been working on that. I’ve also got about a third of the novel that will come after King Sorrow’s written. That’s a book called Hunger. So King Sorrow and Hunger are the two things I’m working on right now.

It’s a pleasure to have a hand in Wolverton Station, which was adapted by Jason Ciaramella, who is a terrific comic writer. A guy who literally was nominated for an Eisner Award with his first ever comic. He wrote an adaptation of “The Cape,” another of my stories, that was instantly nominated as “Best Single Issue.” So he’s really capable.

In a lot of ways, I’m sort of out of the comic-writing business for the moment, while I get the next couple of novels written. But, you know, I’m sure I’ll get back, because I have sort of a comic-book imagination. I have trouble staying away.

Whenever you’re ready, we’ll be here. Thank you so much for your time.

It’s a pleasure. Thanks so much.

Creepshow™ © 2023 Cartel Entertainment, LLC. SKYBOUND and all related images are owned by Skybound Entertainment. IMAGE COMICS and all related images are owned by Image Comics, Inc. All rights reserved.